A Cabinet of Curiosities

A room in the Strahov Museum © A. Harrison

A Cabinet of Curiosities — such a delightful term. It embraces all the romance of the gentleman (or gentlewoman) collector, from parish curates to kings. A time just before the birth of scientific classification, when unicorns and mermaids might still exist, if one was to travel and explore far enough. A time which flows in a direct line to modern museums.

In a city with so much to see, Prague’s Strahov Monastery was a spectacular — and tranquil — find. Paths filled with flowers and birdsong meander past the white monastery buildings; there was an even a place offering accommodation (I noted down the details for next time).

The monastery library consists of a series of rooms with polished bookcases rising to the ceiling. Frescoes adorn the ceilings, sunlight streams through the windows, and any spare space on the walls is covered with parquetry. (I must admit, I did wonder if anyone ever reads the books resting at ceiling height.)

Two rooms and a corridor are dedicated to the monastery’s Cabinet of Curiosities, many appropriately displayed in small cabinets. Most were purchased from the estate of a Baron Karel Jan Eben in 1798, (any further details remain elusive). They include some elephant trunks, a unicorn horn (most likely from a narwhale) and remnants of a dodo. On the wall are a 17th century suite of armour and some chain mail dating from the 12th century.

There’s also a collection of sea animals, from giant crabs to sea shells and everything in between, as well as a range of exotic fruits. Insects are meticulously pinned out for display. Somehow it all makes an harmonious whole, with no arbitrary divisions between displays.

The Baron was obviously interested in military history, for the collection includes the barrel of a cannon and some cannon balls from 1686, a Tartar crossbow and various military helmets, swords, rapiers and a chain mail shirt made from interlocking iron rings.

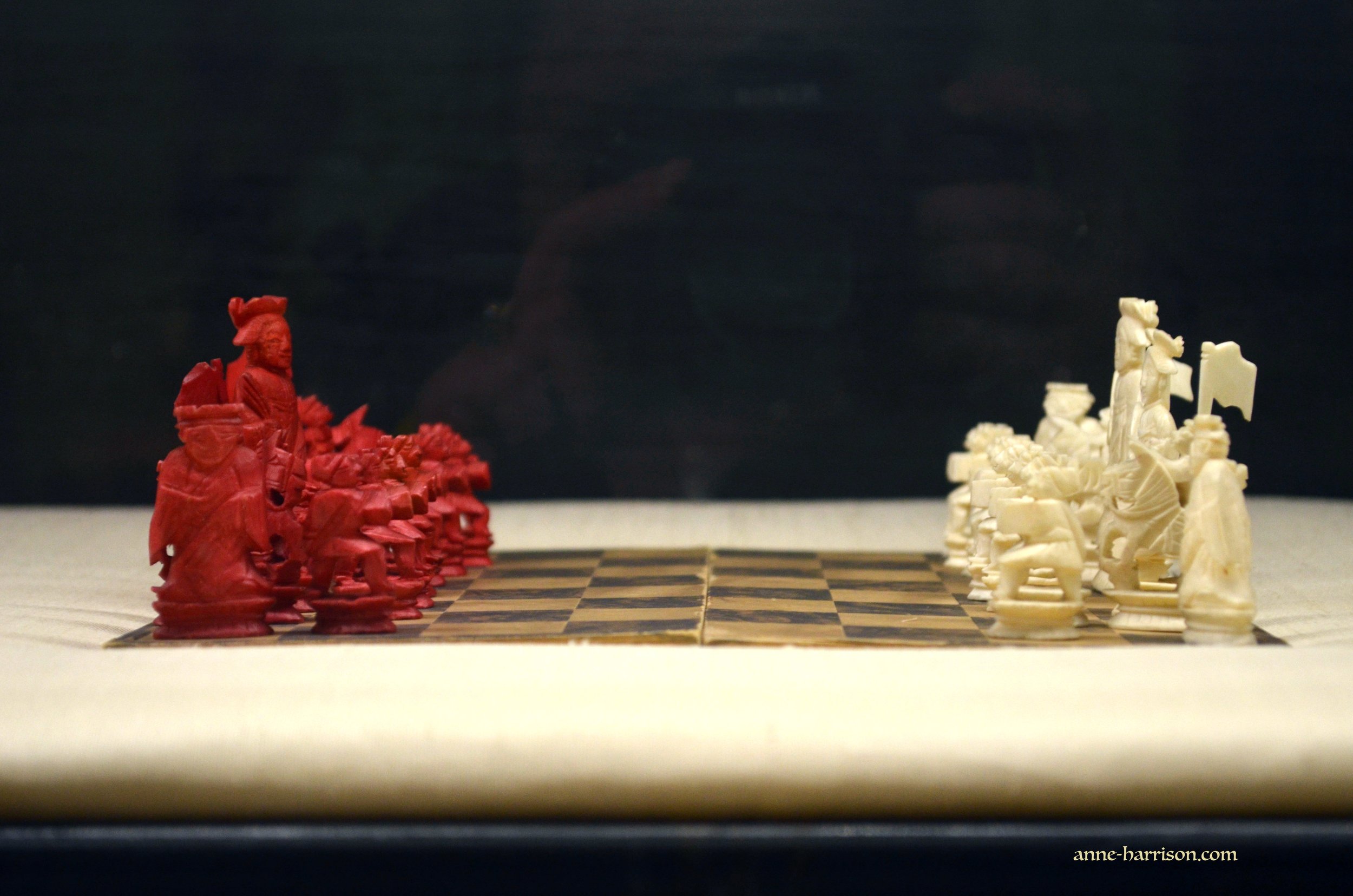

Part of the military display © A. Harrison

Within the Theological hall are a number of both astronomical and terrestrial globes, all works of art in themselves. There is also a xylotheca — 68 volumes documenting a species of wood, the plates made from the appropriate wood for that volume. Inside are roots, branches, leaves, fruits — even insects — pertaining to the tree producing the wood. Something, I have to admit, I had never even heard of, let alone seen before!

There is also a collection of the grotesquely shrivelled remains of sharks, skates, turtles and other sea creatures. These flayed and splayed corpses were prepared by sailors, who passed them off to credulous landlubbers as ‘sea monsters’. Lying on a table to the right of the entrance are two long, brown, leathery things. I had no idea until I read the sign: preserved whale penises.

Then, of course, come the relics. Everywhere in Prague, it seems, has relics, often with a piece of bone clearly visible in its case of gem-encrusted crystal. I’ve seen (and tried to avoid) such a flood of relics across Europe, and I can’t help but wonder how many graves were desecrated. The trade for them must’ve been astronomical. (A small example: Louis IX built Sainte-Chapelle in Paris to house both a piece of the True Cross and the Crown of Thorns. He had acquired these from the Baldwin II, the Latin Emperor of Constantinople, for 135,000 livres; the construction of the chapel cost only 60,000 livres.)

Aside from those books in the library, there are also exquisitely illustrated manuscripts and incunabula (a book printed before 1500) and in these cabinets. How I would love to own even one! Then there was this delightful chess set I came across.

Such a jumble of amazing things, a true Cabinet of Curiosities. If only I could boast something similar in the chaos of my home.

A gorgeous chess set (though, unfortunately, made from ivory) © A. Harrison

Enjoy my writing? Please subscribe here to follow my blog. Or perhaps you’d like to buy me a coffee? (Or a pony?)

If you like my photos please click either here or on the link in my header to buy (or simply browse) my photos. Or else, please click here to buy either my poetry or novel ebooks. I even have a YouTube channel. Thank you!

Plus, this post may contain affiliate links, from which I (potentially) earn a small commission.

The Literary Traveller

Like much of Kafka's writings, The Castle can prove an acquired taste, but Prague is the perfect place to tackle both Kafka and his works. Prague was Kafka's city He was born here in 1883, and a museum dedicated to him is in the Malá Strana, or the Little Quarter.

The novel's protagonist is known only as K; he arrives in a village, and the novel is spent as he tries to gain access to the castle from which the place is governed. It is a surrealistic work, emphasised by the fact Kafka died of TB in a sanatorium before finishing it.

The people of the castle live in a remote world of 'perfect' bureaucracy; they govern the town below, yet do not physically interact with the townsfolk. K enters a world of unknown rules and laws, of solitude and alienation and unexpected companionship. He never enters the castle, he fails to bond with the townsfolk, and yet he cannot return home. During his labyrinthine wanderings, K comes to question the existential meaning of existence.

Like his earlier works, the Castle explores our alienation from an omnipotent yet unseen authority, which is forever protected by a bureaucracy which runs to its own convoluted, illogical and ultimately unknowable rules. The individual is lost, helpless against an alienating world.